Innovation Management

If an innovation is an idea that has been refined so that money can be made from it, then managing innovation is managing the walk from idea to profit. Managing, in turn, includes making choices. Choices that must be made are for example:

- How much do we invest in innovation (money, people, time, equipment, physical environment)?

- Which ideas do we put forward, i.e. take into refinement?

- How long do we work with a certain development process; in what time does an innovation have to “fly”, make money? Compare stage-gate process.

- Who do we co-operate with? Compare open innovation.

The questions can, at least partly, be answered by thinking about the organisation’s strategy; what is our innovation strategy?

For example, deciding on when to launch new products is a strategical question. A shorter interval between new products probably means more people and/or more money working with an innovation.

Another strategical question is the degree of openness in innovation work – do we, like Linux, go for total openness, or do we develop everything inhouse, under strict secrecy?

If, and when, an organization notices that their current innovation strategy does not work, e.g. if the process takes too much resources, new questions need to be solved:

- Shall we open up our ideas for other organisations, thus getting resources from elsewhere?

- Could spin offs continue developing ideas? And can the spin offs be strongly attached to the mother organization? If yes, then how, and how strongly attached?

- Maybe our organisation should not work with innovations?

Managing innovation is about taking decisions. The organisation’s strategy provides guidance, but a strategy can also be changed.

Leadership and Innovation

Leadership should support innovation. This is probably easier said than done. Leadership is a key ingredient within an organisation that wants to be innovative. Leadership takes place inside the own organisation and affects the outcomes of the organisation’s activities.

Without leadership that supports innovation, innovating will not happen to the same extent. It is easy to recognize leadership that is not supportive, but the opposite is maybe more difficult to specify in one sentence.

In the video “If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen ” for example, we see a foreman in a restaurant context, who demonstrates an efficient way of stopping all innovation activities for at least a near future.

Inspiration for Reflection and Discussion

In many discussions on leadership, communication skills come into focus. In organisations, innovation leadership should include, for example:

- Describing what innovation means in the organisation. Do we work with new technical inventions, service processes, or ways of organising work? There are many more innovation types, some of which are introduced in this graphic.

- Motivating and inspiring employees to participate

- Choosing examples of excellent and suitable innovations and demonstrate them to the organisation.

- Verbalising risk levels, e.g. answering questions like “is it alright if I fail, and how much time can I use for an idea, and fail…”

- Stimulating overall discussion about innovation within the organisation.

You can probably think of more issues to discuss – leadership can be a long and winding road!

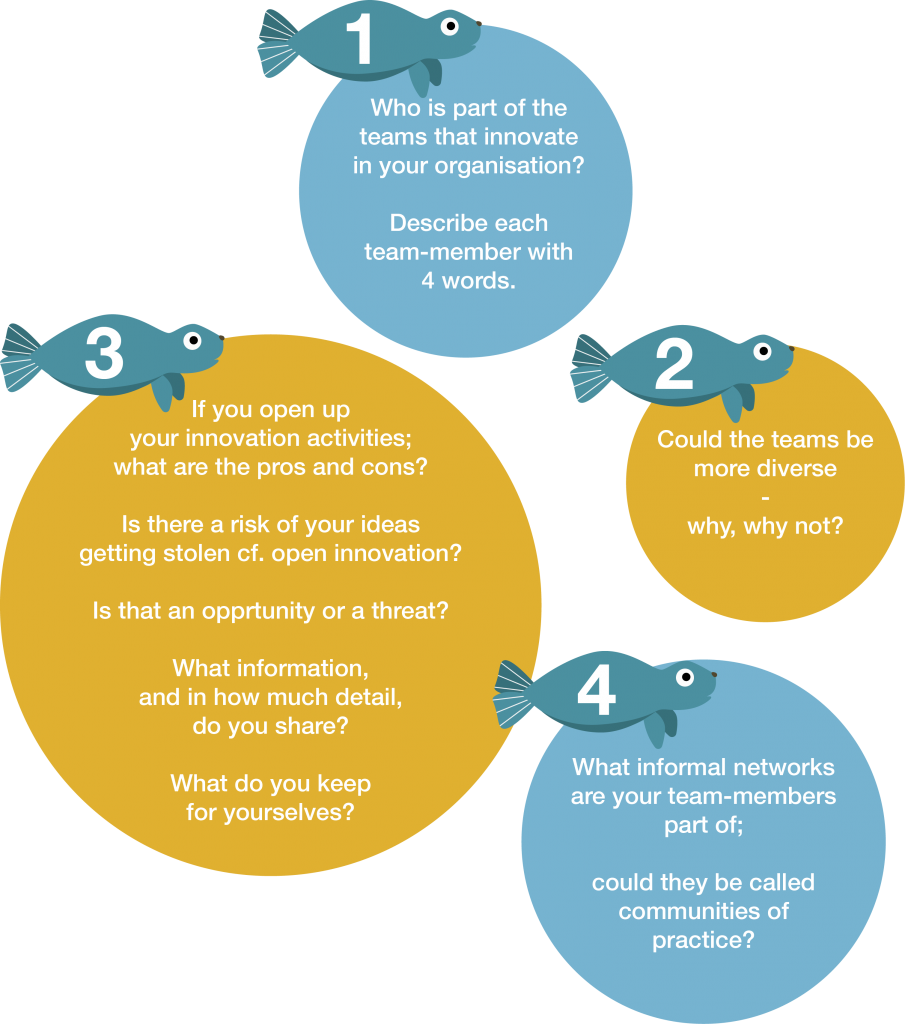

Who?

When looking for advice for creating an innovative team, you will most certainly run in to the concept of diversity; a less diverse team is less innovative, is what the advice says. In some cases, this is self-evident – it is a good idea to include a vegan in the team, when planning the menu for e.g. an international airline.

Diversity is not only the usually understood dimensions such as, gender, age, or religion, but also the backgrounds of the team members.

Adding a female woodworker to a group of male woodworkers of course increases diversity, but adding a designer or art historian may increase innovation capability even further. The idea is to expand the bubbles of similar people that we tend to form, we i.e. like to interact with people who share our opinions and ideas. But sometimes new perspectives and ideas are needed for introducing new ways of thinking.

Small organisations cannot always hire a diverse mix of people, so other ways of including different points of views must be found. Cooperation with other organisations or people outside one’s own organisation, is one way of developing own more diverse thinking. Often, so-called communities of practice, consisting of people interested in similar questions or interests, come to life.

The people involved in the cluster interact also in informal projects, such as this, the IRM-Tool project, thus being involved also in less formal cooperation. The less formal interaction can be called a CoP, and also people from outside the cluster, or from the outer boundaries of it, can join the CoP. Also, people from outside the cluster can form CoPs. For example, a group of artists who are passionate about cruise vessels, can come together in a CoP; they can for example all design phantasy cruise ships or similar, and could thus contribute to ship design. And when a naval architect finds her way into that community of artists, their phantasies might become true. Such communities of practice (CoP) could, for example, easily be imagined within and outside the ship-building cluster in the Turku area in Finland. The cluster includes several companies, universities as well as regulatory organisations.

Inspiration for Reflection and Discussion

As we can read in the figure, finding a balance between open and closed innovation can be difficult. Some of the difficulties are demonstrated in the video Between the Lines.